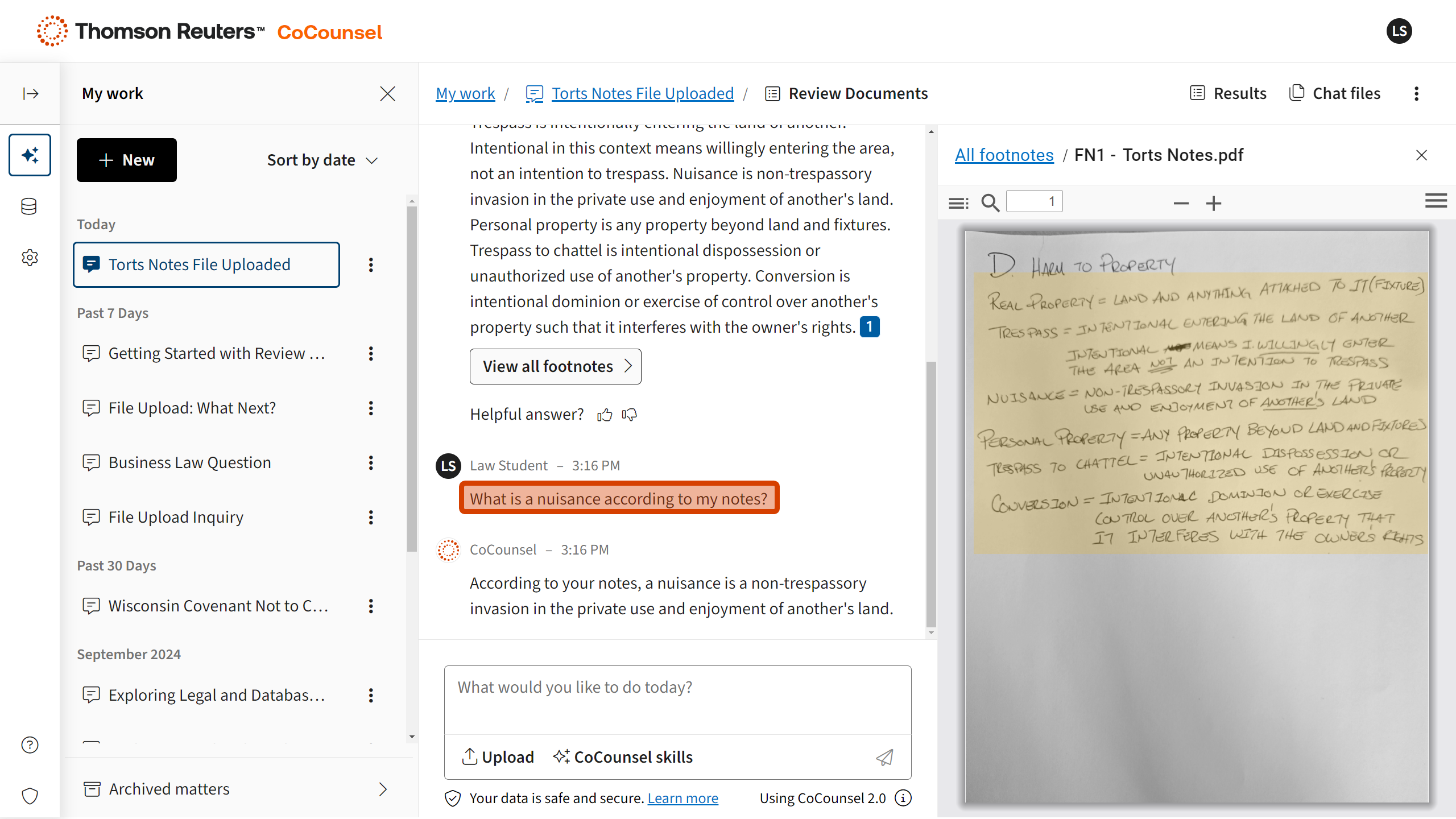

LAW SCHOOL Survival Guide

Torts

Resources to help you succeed in class and on the exam.

Torts: Rules & Guides

Know the rules. Enhance your understanding.

Restatement (Second) of Torts

Dobbs' Law of Torts

Dobbs' Law of Torts provides authoritative, comprehensive, and up-to-date discussion and analysis of the legal principles and rules governing tort law.

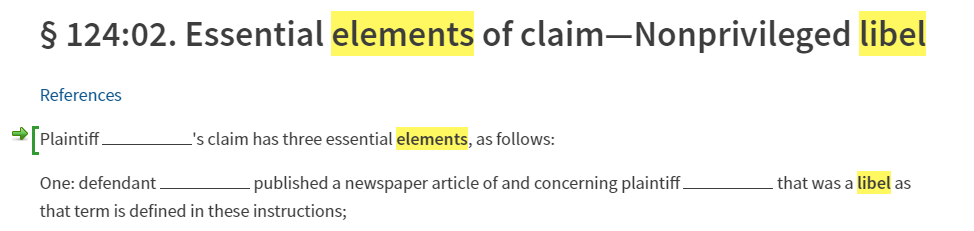

Law of Defamation

The Law of Defamation provides step-by-step guidance to all aspects of modern libel law, First Amendment issues, and libel litigation. Includes checklists and charts.

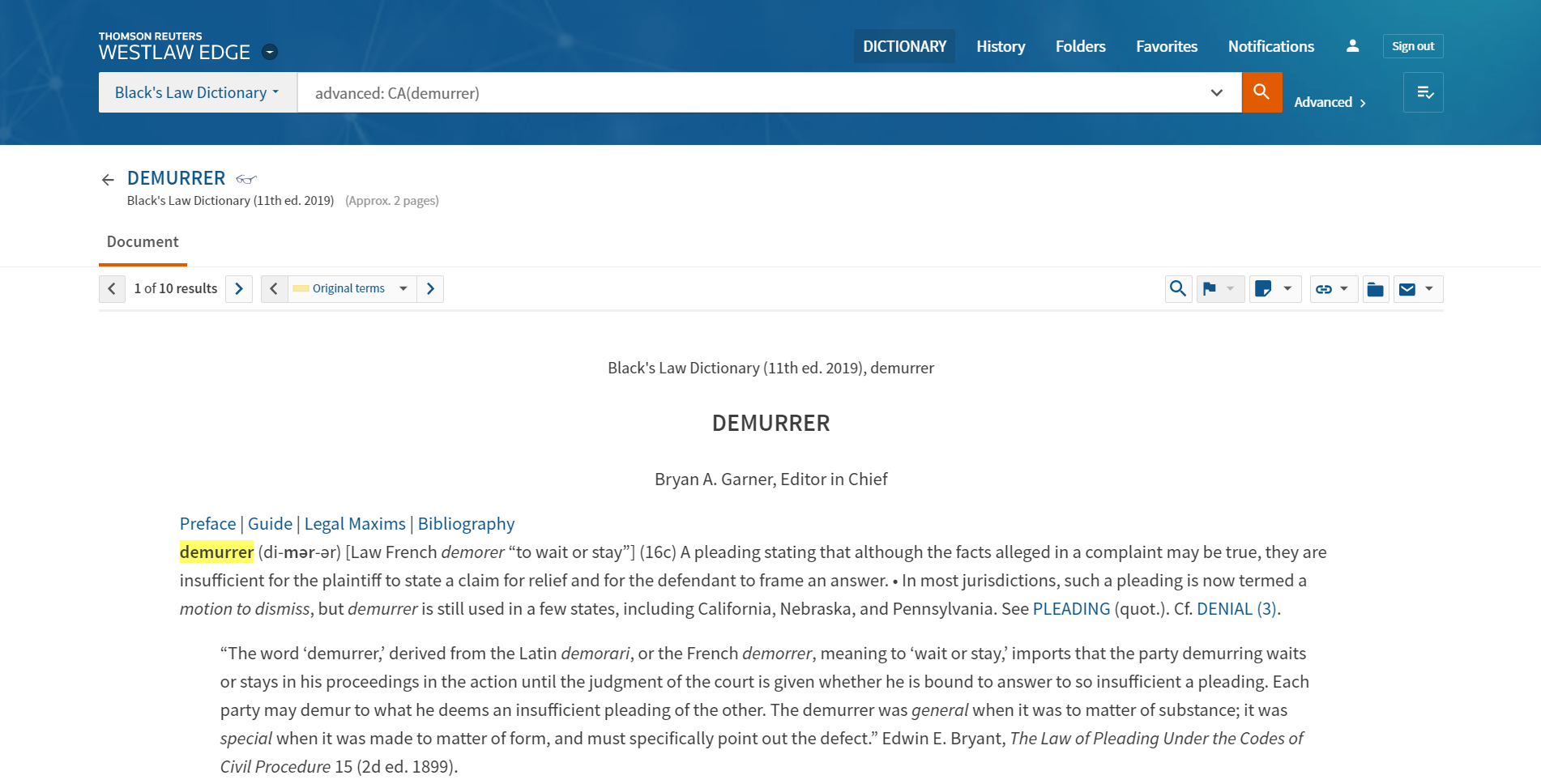

Westlaw

Modern Tort Law: Liability & Litigation 2d

Modern Tort Law: Liability and Litigation provides attorneys with the starting point for any tort research to determine whether a cause of action exists, and the ready insights and analysis they need to answer difficult questions and craft winning legal arguments after they take the case.

Black Letter Outlines: Torts

POWERED BY QUIMBEE

9 min.

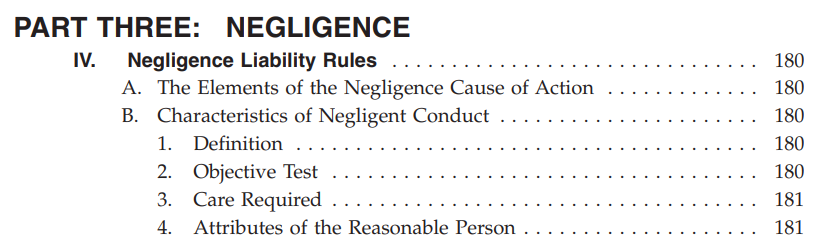

Elements of Negligence

Learn about the required elements necessary to prove negligence, including the duty of care, breach of duty, actual and proximate causation, and actual harm.

POWERED BY QUIMBEE

5 min.

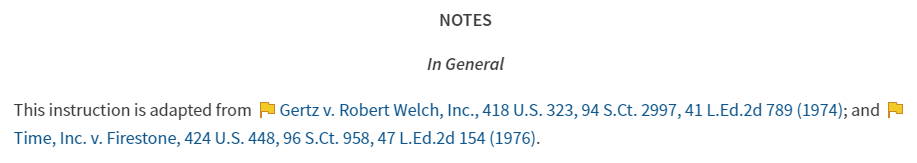

Case Brief Video:

Palsgraf v. Long island Railroad

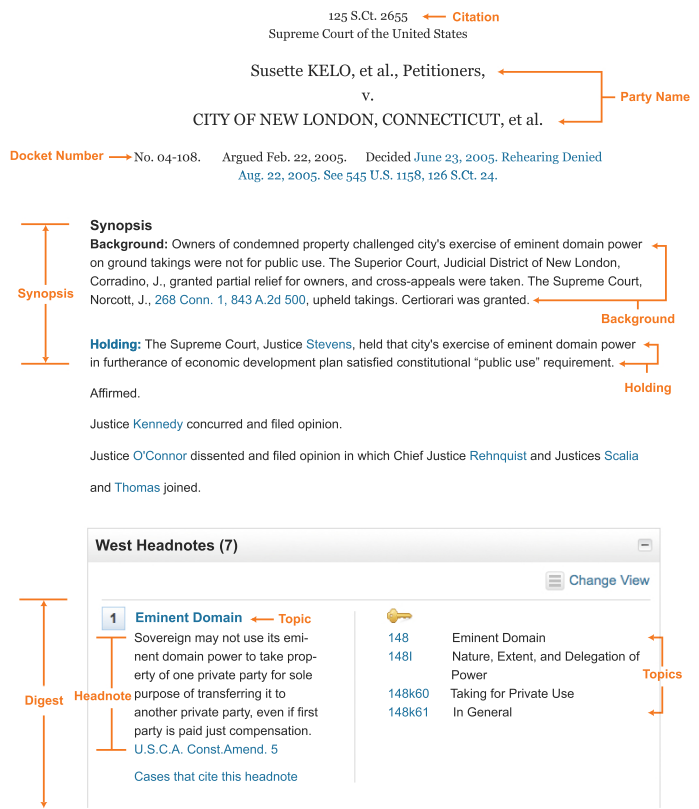

Rule of Law

A defendant owes a duty of care to a plaintiff only if the plaintiff is in the zone of reasonably foreseeable harm resulting from the defendant's actions.

Palsgraf Issue, Holding, & Reasoning

Rule of Law

A defendant owes a duty of care to a plaintiff only if the plaintiff is in the zone of reasonably foreseeable harm resulting from the defendant's actions.

Facts

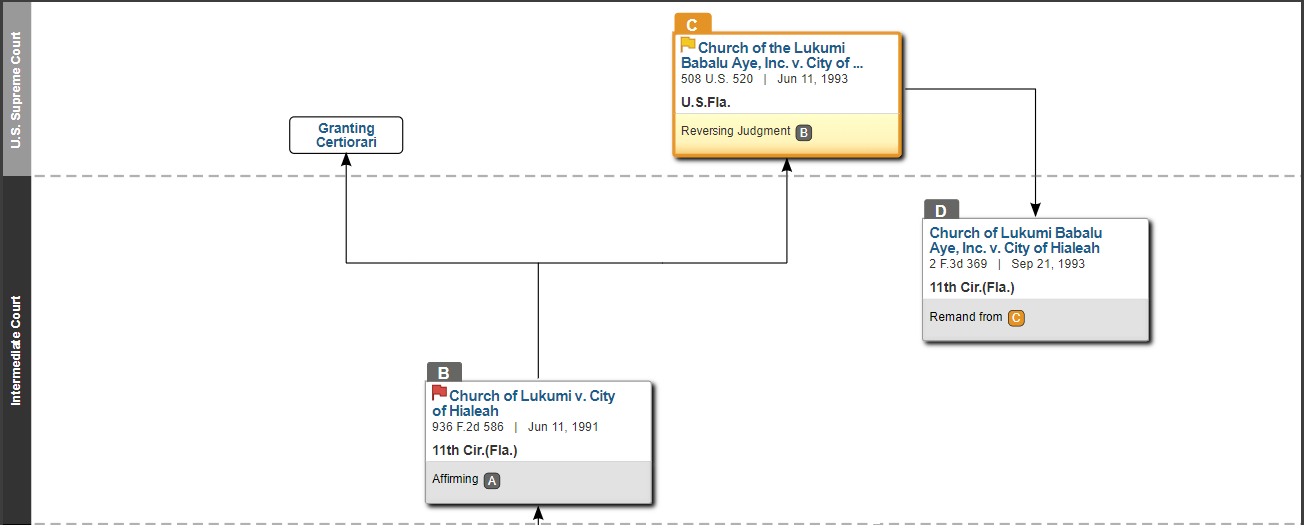

Helen Palsgraf (plaintiff) was standing on a platform owned by the Long Island R.R. (railroad) (defendant). While she was waiting to catch a train, a different train bound for another destination stopped at the station. Two men ran to catch the train as it was moving away from the station. One of the men was carrying a package that, unbeknownst to anyone on the platform, contained fireworks. The first man jumped aboard the train safely, but the man with the package had difficulty. Two train employees helped the man get on the train. However, in the process, the man dropped the package. It fell to the rails and exploded, causing several scales at the other end of the platform to dislodge and injure Palsgraf. Palsgraf brought suit against the railroad for negligence. The trial court granted judgment for Palsgraf, and the appellate division affirmed. The railroad appealed to the New York Court of Appeals.

Issue

Does a defendant owe a duty of care to a plaintiff if the plaintiff is not in the zone of reasonably foreseeable harm resulting from the defendant's actions?

Holding and Reasoning (Cardozo, C.J.)

No. Negligence liability is predicated on the breach of a duty owed by the defendant to the plaintiff. The scope of a defendant's duty is defined by the scope of the reasonably foreseeable harm resulting from the defendant's actions. If someone is outside of the range of the reasonably foreseeable consequences of the defendant's actions, the defendant generally does not owe that person a duty, and the person therefore may not bring a negligence action against the defendant. The range of reasonably foreseeable harm may be a question either for the court or for a jury to decide. Moreover, with regard to identifying the appropriate scope of negligence liability, a plaintiff may not sue on behalf of the risk of injury or bodily harm perpetrated against another; rather, the plaintiff may only recover for harm committed against the plaintiff's own person or property. Here, the railroad employees were attempting to help the man with the package safely board the train. The man suffered no bodily injury in the process, and to the extent he suffered any harm at all, it was only the damage to the package. If anyone could potentially bring a negligence action against the railroad, it would be the man, but he is not doing so. Rather, Palsgraf is bringing an action for her own bodily harm based on the events set in motion when the package dropped. However, this harm to Palsgraf was not reasonably foreseeable. From the outside, the package gave no indication that it contained fireworks; it looked harmless. Given the package's appearance, even if a railroad employee had knowingly and deliberately thrown the package down, this could not be seen as an unlawful act that would put Palsgraf in danger. The consequences should not be more severe for the employee's unintentional conduct. Because the harm to Palsgraf was outside the realm of reasonably foreseeable consequences from the railroad employees' actions, there is no basis for negligence liability in this matter. The decision of the appellate court is reversed.

Dissent (Andrews, J.)

The railroad employee negligently caused a package full of explosives to fall from the arms of a man he was helping. Negligence is an act or omission which unreasonably does or may affect the rights of others. It is incorrect to state that one only has a duty to protect some individuals from the consequences of wrongful acts. One does not only have a legal duty to protect those in a nearby “zone of danger” from harmful acts; rather, one has a duty to protect society at large. Phrased differently, everyone owes the general public the duty of refraining from acts that may unreasonably threaten the safety of others. However, this is not enough to support a theory of recovery for damages against a negligent defendant. To recover damages, the defendant’s negligent act must have been the proximate cause of the plaintiff’s injury. This means that there is a natural and continuous sequence between cause and effect, with few if any intervening causes. In the case of Palsgraf’s injuries, she was standing on the train platform when the railroad employee negligently dropped the package. But for his dropping the package and it exploding, Palsgraf would not have been injured. There is thus a natural and continuous sequence of events between dropping the package and the injury, with no intervening events. The judgment against the railroad should be affirmed.

Powered by Quimbee

Torts: Sample Exam

30 Minutes

Fact Pattern

The plaintiff, P, is a truck driver for a logging company. The logging company has a contract with a rail carrier, calling for the carrier to transport the company’s logs, by train, to various sawmills for processing. The carrier operates out of a railway depot, which a third-party landlord owns and manages.

The depot contains numerous sections of track, and all these tracks are interconnected. Carriers use the tracks to load, unload, and move freight. At least 50 different carriers use the depot, and at any given time, at least 20 of them are actively moving rail cars around the tracks. During loading, a track switch normally protects a given train, by preventing other cars from accessing the track on which the train sits. From a central control room, the depot’s employees control the configuration of the switches and the movement of cars through the depot.

One day, P drives a truck full of logs to the depot. He parks the truck in a staging area, which is a concrete pad next to a section of track. A line of cars sits on the track, and at the back of the line is a flatbed car that holds a crane. The carrier owns and operates all these cars. During loading, the crane lifts the logs from the truck and places them on an adjacent car for transport.

After parking the truck, P exits to speak to the crane operator. The operator tells P, “Stand back while I load these.” P then walks to a space approximately 20 feet away, while the crane operator begins to move the logs. After about 10 minutes, P remembers that he left his cigarettes in the truck’s cab. He walks back to the truck and climbs into the cab to look for them.

At that moment, a log falls from the crane onto the cab, crushing the windshield and caving in the roof. P survives, but he is badly injured. P sues both the depot and the carrier for personal injury. Before trial, the depot settles, without admitting fault. The case then goes to trial against the carrier alone.

At the trial, P testifies that he does not recall the accident. The crane operator testifies that he told P to stay back during loading. The operator also testifies that, as he was lifting the log, a hard jolt caused the crane arm to flex and release the log, which then fell onto P’s truck. Additionally, the jolt caused the crane operator to strike his head against the crane’s control board, knocking him out. Thus, the operator does not remember anything else about the accident.

Finally, another employee of the carrier testifies that she was some distance away when she saw the log fall, at which time she rushed to the scene. There, she saw the crane car sandwiched between (1) the back of the carrier’s train and (2) three other rail cars that did not belong to the carrier. According to this employee, these three rogue cars collided with the crane car, and this was the cause of the accident. This employee also testifies that at least 20 other carriers were actively moving cars around the depot when the accident occurred.

At the close of evidence, P asks for a jury instruction on res ipsa loquitur. The carrier objects.

Should the judge instruct the jury on res ipsa loquitur? Explain.

The judge should not give P’s requested jury instruction on res ipsa loquitur, for two reasons. First, the carrier did not have sufficient control of the track section to justify a permissive inference that the carrier was negligent. Second, P contributed to the injury through his own behavior.

Res ipsa loquitur is a doctrine of proof. In certain circumstances, it enables a plaintiff to rely solely on the occurrence of the injury to show negligence. The theory behind this doctrine is that certain kinds of events generally do not occur without negligence, such that the very occurrence of the accident is evidence of negligence.

Traditionally, for the judge to instruct the jury on res ipsa loquitur, the plaintiff must satisfy the following elements: (1) the harmful event is one that usually does not occur without negligence; (2) at the time of the injury, the defendant had exclusive control of the harmful instrumentality; and (3) the plaintiff’s own actions did not contribute to the harm.

But modern courts often treat the second and third elements of res ipsa loquitur more flexibly than the traditional formulation would suggest. The first element remains largely unchanged: the plaintiff must still show that the harmful event usually does not occur without negligence. Even so, the second element, exclusive control, has relaxed to require only a showing that the defendant was probably responsible for the accident.

The third element has also softened, with the rise of comparative negligence. That is, many courts in comparative-negligence jurisdictions allow a plaintiff to invoke res ipsa loquitur even if the plaintiff was partly at fault for the accident. However, these courts will reduce the plaintiff’s recovery proportionately to the plaintiff’s share of fault. Further, a modified comparative-negligence jurisdiction may bar recovery entirely, where the plaintiff is found to be more than 50 percent at fault.

In most courts, res ipsa loquitur permits the jury to find negligence, but it does not require such a finding if the jury is unpersuaded. Nevertheless, the doctrine can greatly assist a plaintiff in making sure that the case is at least submitted to the jury for decision. That is, because res ipsa loquitur satisfies the plaintiff’s burden of production, it enables the plaintiff to survive dispositive motions like motions to dismiss or motions for summary judgment.

Here, P probably cannot satisfy either the traditional version or the modern version of res ipsa loquitur. Although the accident probably would not have occurred without negligence, the carrier’s fault is too uncertain to satisfy either version. Moreover, P cannot satisfy the third element of the traditional test, because P’s own actions contributed to the accident.

Again, the first element, under either version, is that the accident must be one that normally would not occur without negligence. That is probably true of the falling log here. The log was being moved via a controlled, mechanical procedure that did not appear to be inherently subject to random failure. Indeed, it took the application of an outside force, a collision by the three rogue rail cars, to cause the log to fall. The rogue cars themselves were mechanical devices that could be controlled, whether by using the track switches or by some other means. This indicates that their presence on the carrier’s section of track, along with the resulting accident, was the result of someone’s negligence in managing the track or the cars.

In addition, as a matter of precedent, falling objects have been subject to res ipsa loquitur since the doctrine was first conceived in Byrne v. Boadle, the famous English case of the falling flour barrel. Thus, assessing the facts and applying precedent, one can reasonably say that a log generally does not fall from a crane without negligence. The first element of res ipsa loquitur is therefore satisfied.

The second element, however, is probably not met under either the traditional or the modern formulation. The traditional test states that the harmful instrumentality must have been within the defendant’s exclusive control at the time of the accident. One might be tempted to say that the log was the harmful instrumentality, and that it was within the carrier’s exclusive control, because the carrier’s crane was holding it when the accident occurred. However, this view of things is oversimplified.

The falling log was merely the end result of a larger chain of causation: the log fell because the crane arm flexed; the crane arm flexed because the rogue cars collided with the crane car; and the rogue cars collided with the crane car because they all occupied the same section of track at the same time. It is therefore more accurate to say that the harmful instrumentality was the overall system consisting of the log, the crane, the track on which the crane was sitting, and the rogue cars that came down the track.

Seen in this light, the evidence does not show that the carrier had exclusive control of this system at the time of the accident. To the contrary, the facts state that the depot’s employees controlled the switches that would have isolated the carrier’s section of the track. Those employees also directed the movement of the other 19 carriers, who were then moving cars around the depot. And while the evidence does not address this point, one of the other carriers acting on its own could have done something to cause its cars to encroach upon the carrier’s section of the track. Far from having exclusive control of the track section, then, the carrier appears to have had little or no control. For this reason, P cannot satisfy the second element of res ipsa loquitur under the traditional test.

The result is the same, even if the court applies the modern, relaxed version of the second element. Using that formulation, P would need to show merely that the carrier was probably responsible for the accident, not that the carrier had exclusive control of the harmful instrumentality or system. But there are simply too many other possibilities to satisfy even this reduced burden.

As explained above, it is possible that (1) the depot failed to control the switch, and (2) the depot, or even one of the 19 other carriers, was responsible for the presence of the rogue cars on the carrier’s section of track. Nor is there any evidence as to what, if anything, the carrier itself was supposed to do to ensure safety. Overall, the evidence offers no way to determine who was most likely responsible for the accident. Thus, P cannot satisfy even the more forgiving version of the second element.

Finally, as to the third element, it appears that P did contribute to the accident, which rules out traditional res ipsa loquitur. During loading, P returned to the truck’s cab to get his cigarettes—despite the crane operator’s warning to stay back, and despite the obvious hazards posed by lifting heavy logs with a crane. P thus contributed to his own injury by knowingly placing himself in harm’s way, so he cannot make the required showing as to the third and final element of the traditional test. (As noted above, under the modern test, P’s contributory negligence would not necessarily bar res ipsa loquitur altogether, but would at least reduce his recoverable damages.)

In conclusion, while the accident was probably the result of somebody’s negligence, P has not sufficiently shown who had control of the harmful instrumentality, or who likely caused the accident. Further, under the traditional test, P cannot show that he himself did not contribute to his injury. P’s request for a jury instruction on res ipsa loquitur should therefore be denied.

Yeah, we love Quimbee too.

We've partnered with Quimbee to bring you content on this page. They make law school study aids, bar prep, and CLE courses you'll actually enjoy.