Anything But Part-Time:

The Unique Challenges of an Evening Student

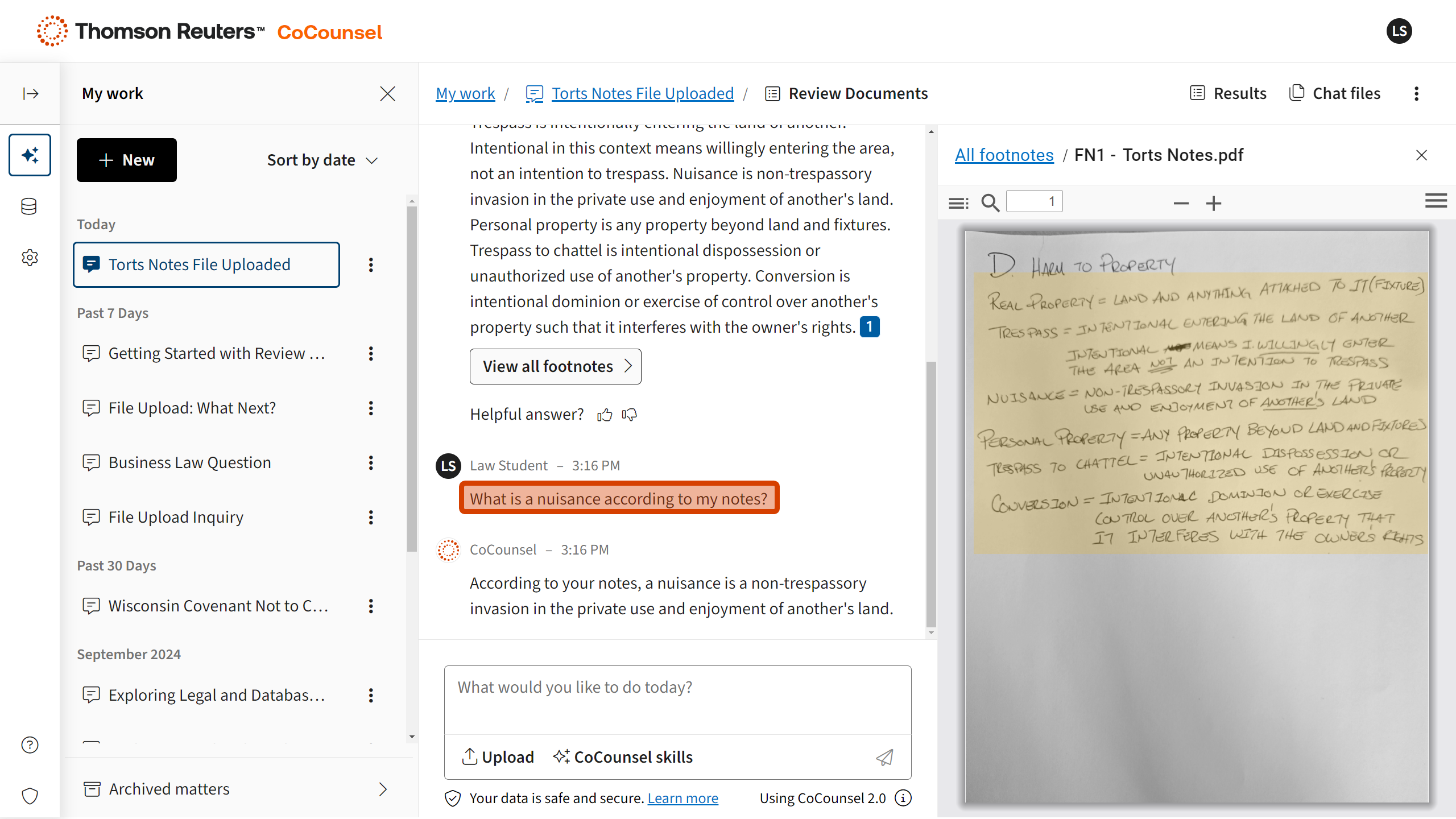

Call me an evening student, say that I attend night school, you can even call me a vampire, but just please do not call me a part-time student. While technically correct, the label of part-time is a disservice to those evening students grinding forward on a different path. Admittedly, evening students carry a lighter course load than full-time students, typically enrolling in three instead of four doctrinal courses in the first year, but evening students must also juggle a full-time day job.

Regardless, I am not here to quibble about semantics, or sell you on the benefits of an evening program (of which there are many). Instead, my goal is to highlight some of the unique challenges faced by evening students.

Life in the Slow Lane: An Extra Year of Law School

Evening students graduate in four years instead of the customary three years. Simply put, your post-graduation plans will need to be delayed for a year.

The extra year, however, affords access to an additional group of classmates to network with and forge relationships. Your classmates today will become your peers, coworkers, and even clients of tomorrow. This is especially true in the tight-knit legal community where relationships matter. Additionally, the extra year can allow you to squeeze in a course with a prestigious professor or participate in a clinic you otherwise could not fit into a three-year schedule. In the event your circumstances change, you can always graduate early by taking extra day courses.

Arrested (1L) Development: Prolonged First-Year Curriculum

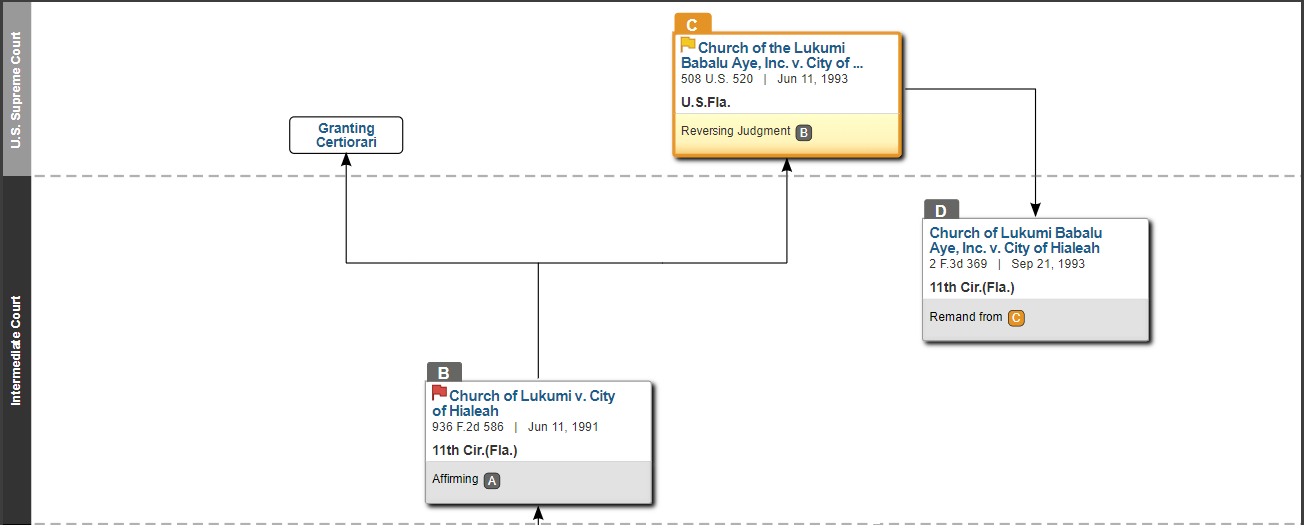

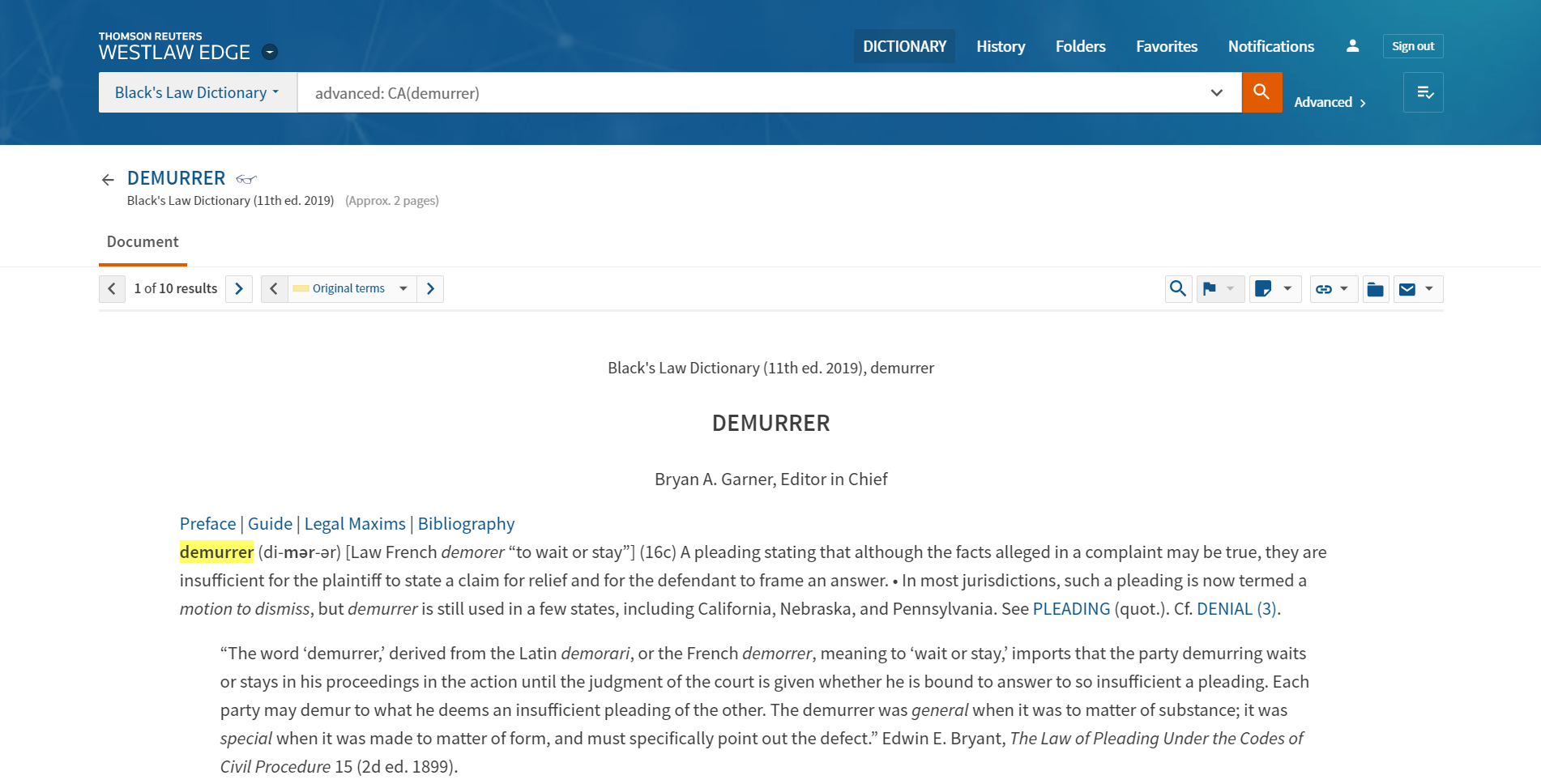

Law school is drenched in tradition—one of which is the stable of first-year courses (Torts, Contracts, Civil Procedure, Constitutional Law, Criminal Law, and Property). For evening students, this 1L curriculum is stretched across three or four semesters instead of two.

This is a disadvantage to evening students in selecting second year elective courses that assume the 1L curriculum has been completed (for instance, I took Administrative Law without the benefit of Constitutional Law). Consequently, an evening student might need to learn the base material in parallel with the more advanced material, but this later becomes an advantage when you finally take the 1L course. Further, keep in mind that scheduling issues are compounded for night students due to the limited availability of evening classes.

Ostensibly, you are in law school at night to upgrade your current job. But the vast majority have a tough decision to make—when should I quit my current job to begin acquiring legal experience?

Let Me Check My Calendar: Activities and Networking Opportunities Are Challenging

Evening students will regularly see advertisements for events they cannot attend. Most events occur during lunch to accommodate day students, and even if there is an evening event, it may still conflict with classes.

There is no sugarcoating it: You will miss many events due to being an evening student, but you can have a comparable experience. First, the marquee law school activities (e.g., journal, moot court, and clinics) are generally available to evening students. Second, a lack of activities is not such a perceived negative for evening students since work experience is a substitute. Finally, a helpful tactic is reaching out to the event organizer or presenter, explaining your situation as an evening student, and asking for the presentation slides or a link to the recording (making a connection in the process). This same principle applies to networking events; the enterprising evening student can email directly and set up a phone or coffee meeting in lieu of attending networking events, ultimately achieving similar (or even better) results.

Making the Grade(s): Extended Hiring Timeline

It is undeniable that first-year grades have an outsized importance in legal hiring. This grade-sensitivity window is extended from one to two years for evening students. Large law firms who hire through the on-campus interview programs typically recruit summer associates after completing your 1L year, but evening students are recruited after their 2L year.

This challenge highlights the mantra that law school is a marathon not a sprint. At the outset, the evening student should be aware that performance must be sustained over four or five semesters instead of just two. On the other hand, this is an opportunity for the evening student to schedule elective courses that align with their strengths and interests, or to demonstrate an upward trend after a challenging first year.

When to Cut the Cord: Leaving Your Current Job to Pursue a Legal Job

Ostensibly, you are in law school at night to upgrade your current job. But the vast majority have a tough decision to make—when should I quit my current job to begin acquiring legal experience?

This can be a delicate question for those with established careers, mortgages, or families that rely on your income. Traditional large firms require participating in a ten-week summer associate program, so you will have to take vacation or unpaid leave from your current job. If that is not possible, then you may need to consider quitting your current job at the end of your third year and finding new employment for your fourth year of law school. Of course, large law firms are just one of many types of employment, but there will always be a tension between cashing checks at your current job versus acquiring legal experience (particularly over the summer) for your future job. If leaving your current job is not an option, consider how you could obtain legal experience at your current employer by offering to assist with legal tasks (or even quasi-legal) or seeking an assignment to the legal department. Whether for a summer associateship, bar prep, or seeking employment as a licensed attorney, the decision to quit your current job is an eventuality that you should plan for as early as possible. But as they say, the best laid plans of mice and men often go awry.

Stephen Nasko is a third-year evening student at Georgetown University Law Center where he is an Administrative Editor for The Georgetown Law Journal and a member of the moot court team. Stephen has worked as an analyst for the Department of Justice since