LAW SCHOOL Survival Guide

Contracts

Resources to help you succeed in class and on the exam.

Contracts: Rules & Guides

Know the rules. Enhance your understanding.

Restatement (Second)

of Contracts

Restatement (Second) of Contracts | Index

UCC Article 2

Sales

Practical Law

Contracts Course Study Collection

A collection of Practical Law resources about topics that are commonly covered by Contracts law school courses.

POWERED BY QUIMBEE

7 min.

Learn About Consideration

Learn about what constitutes the "something of value" that needs to be exchanged in a bargain in order to form a contract.

POWERED BY QUIMBEE

3 min.

Case Brief Video:

Johnson v. Otterbein University

Rule of Law

A contract promising to pay a sum of money to the promisee and instructing the promisee to use the money in a particular way is unenforceable for lack of consideration.

Johnson Issue, Holding, & Reasoning

Facts

Johnson (plaintiff) provided to Otterbein University (Otterbein) (defendant) a note promising to pay a sum of money for the sole purpose of allowing Otterbein to pay its debt. Johnson did not pay the note. Otterbein brought suit in the court of common pleas. Judgment was entered for Otterbein. Johnson moved for a new trial, but was overruled. Johnson appealed to the district court, which affirmed the court of common pleas. Johnson appealed.

Issue

Is a contract promising to pay a sum of money enforceable because it requires the promisee to use the money in a particular way?

Holding and Reasoning (Martin, J.)

No. An executory contract promising to give something is not based upon consideration. A promise to pay a gift of money may be revoked at any time. A promise must advantage the other contracting party and disadvantage the promising party in order for it to be consideration. Consideration may be a promise, and may create a contract based upon mutual promises. In the current matter, the direction in the document to apply the money in a particular manner is not sufficient to form consideration. Accepting the writing does not create mutual promises. Accordingly, the judgment of the district court is reversed.

Powered by Quimbee

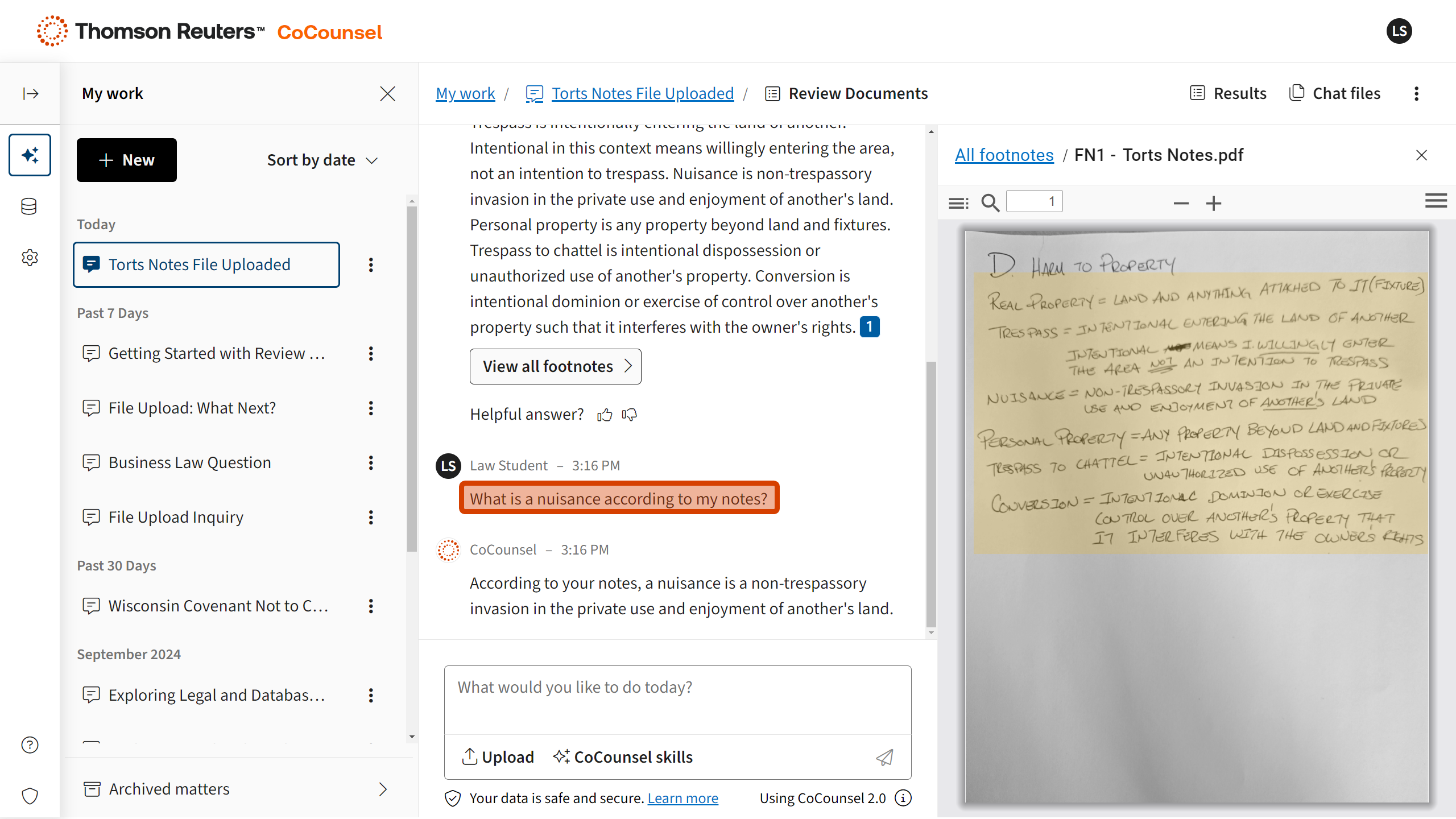

Contracts: Sample Exam

30 Minutes

Fact Pattern

Theater Owner owns and manages the Village Theater. Recently, Theater Owner spoke with Costumer, a local costume designer, about a holiday vocal concert she was planning to host in early December of next year, 14 months away. As the concert was to feature an appearance by Santa Claus, Theater Owner needed a generic Santa costume.

Because Theater Owner planned to hold the holiday concert every year, Costumer suggested that it might make more sense for her to buy the Santa suit, rather than renting one every December. Costumer’s advice made sense to Theater Owner. The two thus orally agreed that Costumer would design and construct a custom-built Santa suit, to be delivered one week prior to the holiday concert, and not before. In exchange, Theater Owner would pay Costumer $500.

However, eight months later, and six months before the concert, the local fire marshal inspected the Village Theater to assess the building’s compliance with recently amended fire regulations. The amendments imposed new and severe requirements regarding access to exits in public venues.

After the inspection, the fire marshal informed Theater Owner that under the amended regulations, the Village Theater’s balcony seats did not have sufficient access to exits. To comply with the regulations, the Village Theater would need additional staircases with exit doors. Without those improvements, Theater Owner could not legally sell tickets to the balcony seats. This reduced the total seating capacity of Village Theater from 500 to 400 seats.

Theater Owner was disappointed to hear the fire marshal’s report, as her profits on the holiday performance would be significantly lower if she could sell a maximum of 400 tickets, as opposed to the 500 she wanted to sell. Thinking it best to make the needed improvements as soon as possible, Theater Owner notified all her vendors, including Costumer, that all upcoming events were canceled until she could finish adding the staircases and exit doors. Soon after, Costumer received another email from Theater Owner, notifying him that she no longer planned to honor their agreement, because she could not complete the needed improvements by the scheduled concert date. Furious, Costumer called Theater Owner to complain, after which he sued Theater Owner for breach of contract.

As to damages: Costumer indicated that he had expected to spend $600 on the raw materials to construct the Santa suit, but had spent only $150 thus far, all on materials that could not be returned or reused.

Assume that the common law of contracts, and not the Uniform Commercial Code, applies here.

What defense(s) to enforceability, if any, will Theater Owner raise as to the form of her contract with Costumer? Will the defense(s) likely succeed? Explain.

Theater Owner will argue, probably successfully, that her agreement with Costumer is unenforceable, because it does not satisfy the Statute of Frauds. A contract falls within the Statute of Frauds if, by its own terms, it cannot be fully performed within one year of its execution. To be enforceable, any contract falling within the Statute of Frauds must be in writing and signed by the party against whom enforcement is sought (sometimes called the party to be charged).

Here, the contract falls within the Statute of Frauds, because it cannot be performed within a year after execution. Theater Owner and Costumer agreed that Costumer would deliver the Santa costume no earlier than one week before the holiday concert, which was scheduled for 14 months after they made the agreement. True, Costumer would likely start work within one year, and he might have even finished the suit within one year. However, the contract, by its terms, could not be fully performed within one year of its execution, because Costumer was not to deliver the suit until 14 months after that time.

Thus, for the contract to be enforceable under the Statute of Frauds, it would need to be written, and Theater Owner, as the defendant, would need to have signed it. However, the agreement was only verbal, so it fails to satisfy the Statute of Frauds and is thus unenforceable.

What defense(s) to enforceability, if any, will Theater Owner raise as to the fire marshal’s report? Will the defense(s) likely succeed? Explain.

Theater Owner will argue that the contract is unenforceable, because her purpose in holding the holiday performance—and, by extension, in contracting for the Santa suit—has been substantially frustrated. The doctrine of frustration of purpose applies where, after formation, intervening circumstances frustrate a main purpose of one party in entering the contract, rendering the other party’s return performance basically worthless.

Under this doctrine, any remaining performances under the contract may be discharged, but only if these elements are satisfied: (1) the frustrated purpose was a main reason one party entered into the contract, (2) the frustration is so severe that it is unreasonable to regard the risk as one the party assumed under the contract, and (3) the reason for the substantial frustration defies a basic assumption upon which the contract was made.

Theater Owner presumably entered into the contract anticipating a profitable holiday concert, so the total number of tickets available to sell was clearly a basic assumption upon which the contract was made. The frustration, however, was that the theater’s seating capacity was reduced from 500 to 400. Unfortunately for Theater Owner, this is likely not a large enough change to amount to frustration of purpose.

Certainly, this change would reduce Theater Owner’s profits, assuming she could sell all available tickets. However, the facts do not indicate that Theater Owner can guarantee selling all tickets available for a given performance. Thus, common sense tells us that not selling some of the tickets—even 20 percent of the tickets, as here—is part of the inherent risk that Theatre Owner assumed in the underlying contract. The reduction of available seats due to the recently amended fire regulations is therefore probably not a justifiable reason to discharge Theater Owner’s contractual obligations.

How would Theater Owner’s argument change if, unbeknownst to Theater Owner, the amendments to the fire code had been passed before Theater Owner and Costumer formed a contract? Explain.

If the amendments to the fire code had been passed before Theater Owner and Costumer entered into the contract, then the issue would be one of unilateral mistake, not frustration of purpose. A contract is unenforceable due to unilateral mistake if these elements are satisfied: one party to a contract was mistaken as to a basic assumption underlying the contract, that mistake materially affected the contract as it concerned the mistaken party, the mistaken party did not bear the risk of the mistake, and enforcing the contract would be unconscionable as a result.

Here, Theater Owner would probably argue that, when she entered the contract, she was unaware of the amended fire regulations and their impact on the number of tickets she could legally sell. Thus, and as explained above, a seating capacity of 500 was a basic assumption underlying the contract. She would then contend that the 20 percent reduction in seating capacity materially affected the contract as to her, making it unconscionable to enforce the contract against her.

Even so, it is unlikely that a reduction in seating capacity from 500 to 400 is so material a change that the contract between Theater Owner and Costumer has become unconscionable. Moreover, it is even clearer that Theater Owner bore the risk of knowing how many tickets to her own theater she could legally sell, as people are generally charged with knowledge of the law. Relatedly, as explained above, Theater Owner assumed the risk that even with full seating capacity, she might not be able to sell all 500 tickets, or even 400 tickets, to the holiday performance. Theater Owner would therefore be unsuccessful in arguing the contract to be unenforceable due to her own unilateral mistake.

Assume that the contract between Theater Owner and Costumer is enforceable. What will Costumer likely receive in damages? Explain.

The issue is how to calculate Costumer’s damages, even though Costumer would have lost money on his contract with Theater Owner, had Theater Owner performed as agreed. Perhaps the most common method of calculating damages is expectation damages. The goal of expectation damages is to give the nonbreaching party the benefit of its bargain, such as the expected profit on the contract.

If there are no expectation damages, however, the nonbreaching party may request reliance damages. These compensate the nonbreaching party for any harm suffered in reliance on the contract; their goal is to place the non-breaching party in the same position as if the contract had never been made. However, if the breaching party can prove that the nonbreaching party would have lost money were the contract fully performed, then the court will deduct the amount of that loss from the nonbreaching party’s reliance damages.

Here, there are no expectation damages, because Costumer did not anticipate a profit or other net benefit on this contract. Accordingly, a court would most likely award Costumer reliance damages, rather than expectation damages. Costumer has shown that he spent only $150 on materials, which he could not return or reuse. Costumer’s initial reliance damages are therefore $150. Even so, Theater Owner can prove that, while she would pay Costumer $500 under the contract, Costumer had expected to spend $600 on the materials needed to perform. Costumer would thus have lost $100 if the contract were fully performed. That $100 will be deducted from his $150 reliance damages, for final reliance damages of $50.

Yeah, we love Quimbee too.

We've partnered with Quimbee to bring you content on this page. They make law school study aids, bar prep, and CLE courses you'll actually enjoy.