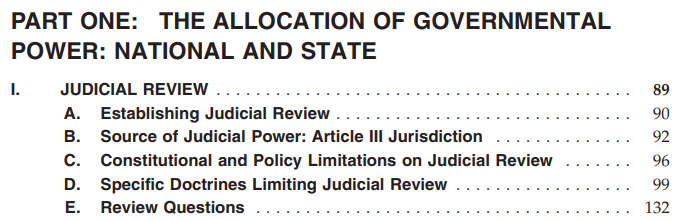

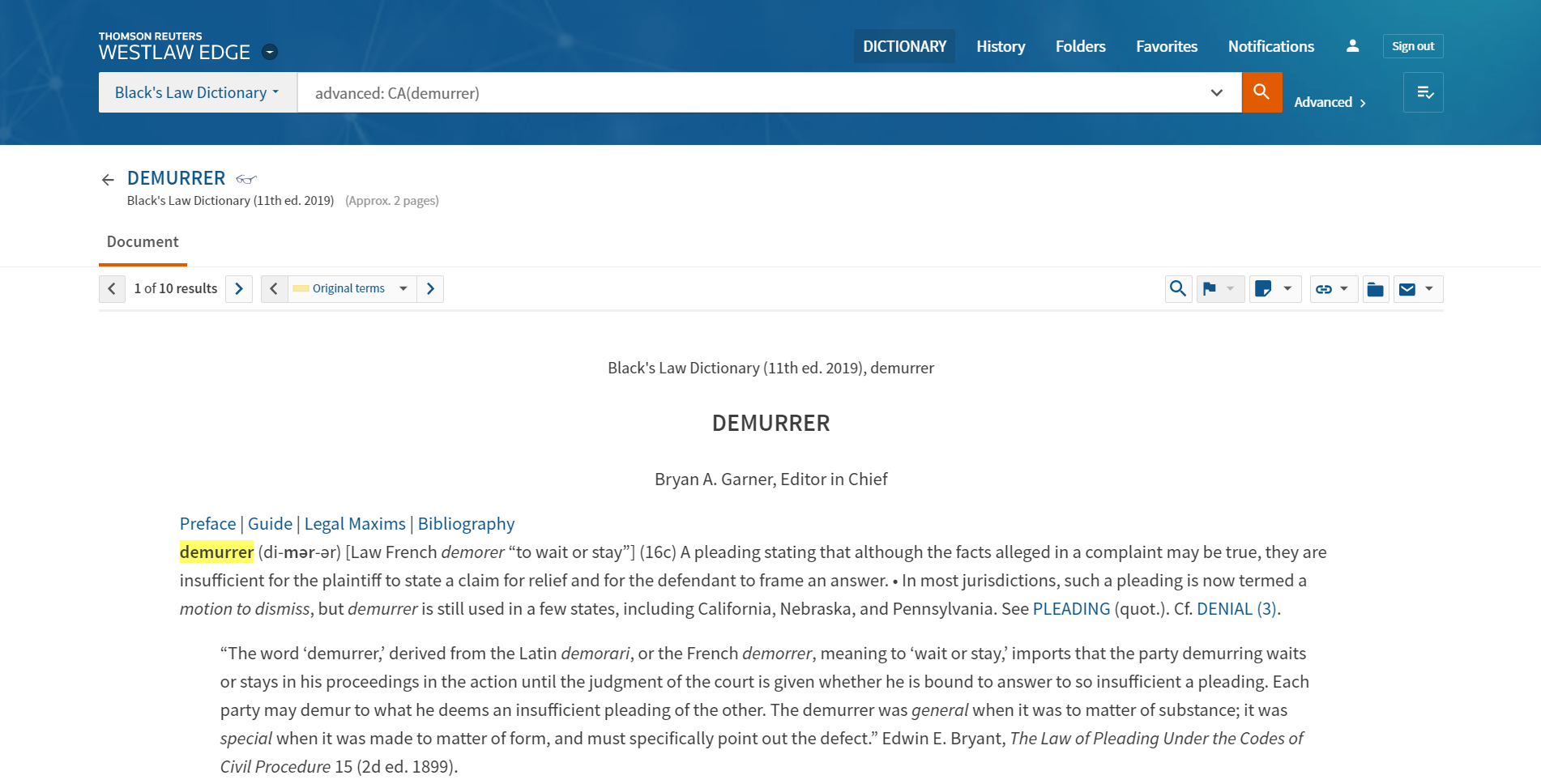

LAW SCHOOL Survival Guide

Constitutional Law

Resources to help you succeed in class and on the exam.

Constitutional law: Rules & Guides

Know the rules. Enhance your understanding.

United States

Constitution

Modern

Constitutional Law

Rotunda and Nowak's Substance & Procedure

Practical Law

Course Study Collection

A list of essential Practical Law resources to help you learn the basics of Constitutional law.

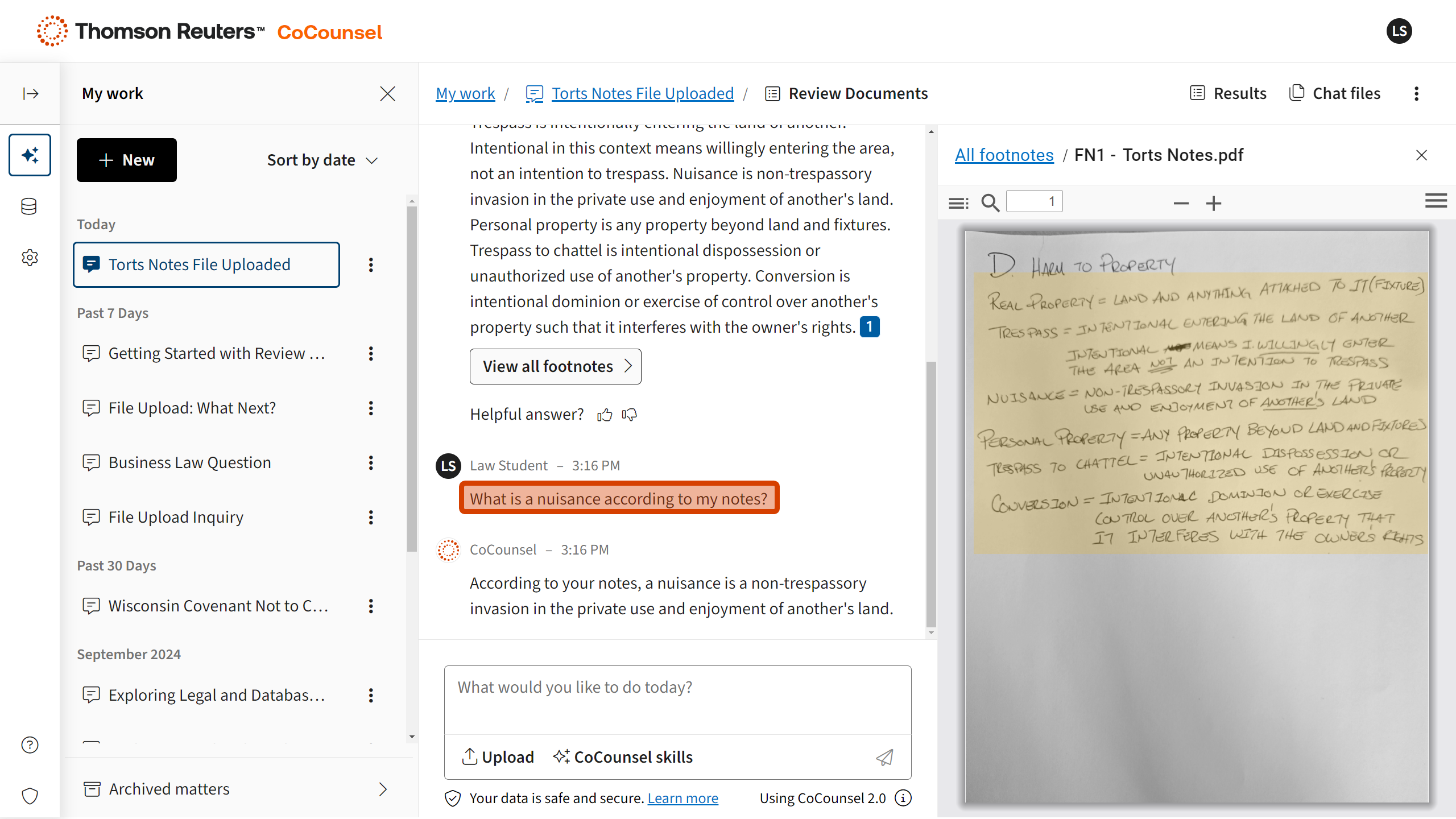

POWERED BY QUIMBEE

7 min.

Explained: Legislative Power

Learn about the Supreme Court’s 1819 decision in McCulloch v. Maryland, and its recognition that the Constitution bestows upon Congress certain implied powers as means toward exercising its enumerated powers.

POWERED BY QUIMBEE

5 min.

Case Brief Video:

United States v. Curtiss-Wright Export Corp.

Rule of Law

An otherwise unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the executive may nevertheless be sustained on the ground that its exclusive goal is to provide relief in a foreign conflict.

Curtiss-Wright Facts, Issue, & Holding

Rule of Law

An otherwise unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the executive may nevertheless be sustained on the ground that its exclusive goal is to provide relief in a foreign conflict.

Facts

Congress passed a resolution authorizing the President to stop the sale of arms to countries involved in the Chaco border dispute. That same day, President Roosevelt issued an executive order prohibiting munitions sales to warring countries involved in the Chaco border dispute. In 1936, an indictment was issued alleging that Curtiss-Wright Export Co. (defendant) illegally sold arms to Bolivia, a country engaged in the Chaco border dispute. The transaction was in violation of the congressional resolution and the President’s executive order. The district court issuing the indictment held for Curtiss-Wright, ruling that the indictment was not supported by sufficient information to charge Curtiss-Wright. The United States government (plaintiff) appealed directly to the United States Supreme Court.

Issue

Whether an otherwise unconstitutional delegation of legislative power to the executive may nevertheless be sustained on the ground that its exclusive goal is to provide relief in a foreign conflict.

Holding and Reasoning (Sutherland, J.)

Yes. There are significant differences in the federal government’s power to regulate internal versus foreign affairs. All powers given to the federal government over internal affairs are carved out by enumerated provisions in the Constitution from the powers generally reserved to the states. In contrast, any powers given to the federal government over foreign affairs are not carved out from state power because the states never possessed powers over foreign affairs. The grant of power over foreign affairs vested in the federal government after it usurped power from the British Crown. The President is the sole organ of the federal government in the field of international relations. Any exercise of power by the President must be exercised within the constitutional parameters granted to him, but the scope of the President’s powers in international affairs is broad. In order to effectively maintain international relations, congressional legislation concerning foreign affairs must accord the President a degree of discretion and freedom from statutory restriction that would not be admissible if domestic affairs alone were involved. The President’s executive order is constitutional and the decision of the district court is reversed.

Powered by Quimbee

Constitutional Law: Sample Exam

30 Minutes

Fact Pattern

In response to an increasing number of motor-vehicle accidents across the nation, the U.S. Congress enacts a federal statute, titled the Don’t Text and Drive Act (the Act). The senate report for the Act attributes the increase in motor-vehicle accidents to a rise in the number of drivers, particularly teenagers, who send and receive text messages while driving. The senate report finds that these accidents cost billions of dollars annually in economic losses, personal injury, and overall societal harm, and that they interfere with the well-being and educational prospects of their teenager victims. The senate report further asserts that this problem requires a national solution, because states have failed to uniformly prohibit texting while driving.

The Act, as explained below, conditions certain federal funding on the states’ prohibiting texting while driving, an offense defined in the Act as “operating a motor vehicle while manually typing or entering multiple letters, numbers, symbols, or other characters into a wireless communications device.” Under the Act, states have the discretion to impose civil or criminal penalties on violators.

Any state that does not prohibit texting while driving will lose 15 percent of the federal funds it receives to improve the quality of its public K-12 education. The total amount that each state would lose constitutes approximately 2 percent of an average state’s overall budget.

Is the Act constitutional? Explain.

The answer is no. Of the five required elements, the Act satisfies four, but fails the requirement that the conditions attached to the federal funding be relevant to Congress’s purpose in granting the funding.

The statute is an attempted exercise of Congress’s power under the Spending Clause, which allows Congress to offer federal funds to the States, subject to the states’ compliance with specified conditions. These kinds of arrangements are constitutional under the Spending Clause if the following five requirements are met: (1) the exercise of the spending power must further the general welfare of the United States, (2) the conditions that states must meet to receive federal funding must be stated unambiguously, (3) the conditions must be related to Congress’s purpose in granting the federal funding, (4) the conditions must not be used to induce states to commit unconstitutional acts, and (5) the financial inducement offered to the states by Congress cannot be so coercive as to pass the point at which pressure turns into compulsion.

Requirement 1

The first issue is whether the exercise of the spending power furthers the general welfare of the United States. In determining whether spending furthers the general welfare, courts largely defer to Congress’s determination. Here, Congress has found that texting while driving has hampered roadway safety and caused an increase in motor-vehicle accidents. Applying a deferential standard, the Act serves the general welfare of the United States because it seeks to promote roadway safety, decrease accidents, and save lives and taxpayer money.

Requirement 2

The second issue is whether the conditions that states must meet, to receive the federal funds, are stated unambiguously. Here, the conditions in the Act are clear. The Act specifically defines the offense that Congress wants the states to prohibit, and it affords the states discretion to impose civil or criminal penalties on the violators.

Requirement 3

The third issue is whether the conditions that states must meet, to receive the federal funding, are related to Congress’s purpose in granting the funding. Specifically, in this case, the question is whether the condition of prohibiting texting while driving relates to Congress’s purpose in providing the states with federal funds for public K-12 education. Although this is a close question, the answer is probably no.

In South Dakota v. Dole, the U.S. Supreme Court held that this requirement was satisfied where the federal government conditioned the receipt of 5 percent of federal highway funding on the requirement that states raise their minimum drinking age to 21. The Court held that the condition was directly related to highway safety, which was a primary purpose for providing federal highway funds, because teenagers were particularly prone to cause accidents after drinking and driving.

Here, the relationship between the spending and the condition in the Act is less direct than the relationship in Dole. At first blush, there is no apparent relationship between funds for education and texting while driving. Educational funds are provided to bolster the quality of public education in the states, and do not bear a direct relationship to highway accidents. Nevertheless, according to the senate report, teenagers are the primary victims in texting-while-driving accidents, which can interfere with the well-being and educational prospects of their teenager victims. This, in turn, relates (albeit indirectly) to the purpose of federal funding for K-12 education, but this relationship is probably too attenuated to satisfy the third requirement. To make the relationship between condition and purpose stronger, Congress should amend the statute to condition the receipt of highway funds, rather than education funds, on prohibiting texting while driving.

Requirement 4

Note: Requirement 4 addresses a First Amendment question, freedom of speech, but the First Amendment is often taught in Constitutional Law II, or perhaps a separate course on the First Amendment. Either of these would probably be an upper-level course. Thus, if your law school separates Constitutional Law into two classes (or teaches First Amendment as a separate class), and you have taken only Constitutional Law I, your answer will understandably not discuss this issue.

The fourth issue is whether the conditions seek to induce the states to do anything unconstitutional. The answer is no, because the states would not forbid a constitutionally protected activity simply by prohibiting texting while driving.

More specifically, the prohibition on texting while driving is a constitutional time, place, and manner restriction on certain communication activities, so it does not run afoul of the First Amendment. For a time, place, and manner restriction to be constitutional, the following requirements must be met: the regulation must serve an important governmental interest, that government interest must be unrelated to the suppression of a particular message, the regulation must be narrowly tailored to serve the government's interest, and the regulation must leave open ample alternative means for communicating messages.

All of these requirements are satisfied here. The regulation furthers the important government interest of promoting roadway safety. The government interest is unrelated to the suppression of a particular message, since the statute is concerned with the means—texting while driving—through which the communication occurs, rather than the content of the communication itself. The statute is narrowly tailored because it prohibits texting while driving, which is the very activity that has led to an increase in motor-vehicle accidents. The statute also leaves open ample alternative means for communicating messages, since citizens are free to send text messages, and communicate via other means, as long as they are not driving. Accordingly, the Act does not require the states to engage in any unconstitutional activity in order to receive funding.

Requirement 5

The fifth issue is whether the financial inducement offered to the states by Congress is so coercive as to pass the point at which pressure turns into compulsion. For the Act to pass this test, the states must have a genuine choice whether to accept Congress’s condition. In South Dakota v. Dole, the Supreme Court held that the condition at issue was not coercive, because the states would lose only 5 percent of their federal highway funds if they refused to raise their minimum drinking age to 21. The federal funds at stake constituted less than 0.5 percent of South Dakota’s budget, which the Court found to be only “relatively minor encouragement.” In contrast, in NFIB v. Sebelius, the Supreme Court held that Congress’s threat to withhold 100 percent of Medicaid funds from states who refused to accept Congress’s new Medicaid program was unconstitutionally coercive. The funds at stake in Sebelius amounted to over 10 percent of a state’s overall budget.

The amount at stake here lies somewhere between the funds at stake in Dole and Sebelius. Particularly, 15 percent of all education funds—which amounts to 2 percent of an average state’s overall budget—is more than the amount in Dole, but less than the amount in Sebelius. Nevertheless, because the amount involved here (2 percent of the overall budget) is closer to the 0.5 percent of the budget at stake in Dole than it is to the 10 percent of the budget at stake in Sebelius, Congress’s financial inducement is probably not coercive.

In conclusion, although the Act satisfies four of the five requirements under the Spending Clause, because the purpose of the federal funding (education) doesn’t bear a sufficiently close relationship to the condition (prohibiting texting while driving), the Act is unconstitutional.

Yeah, we love Quimbee too.

We've partnered with Quimbee to bring you content on this page. They make law school study aids, bar prep, and CLE courses you'll actually enjoy.