LAW SCHOOL Survival Guide

Civil Procedure

Resources to help you succeed in class and on the exam.

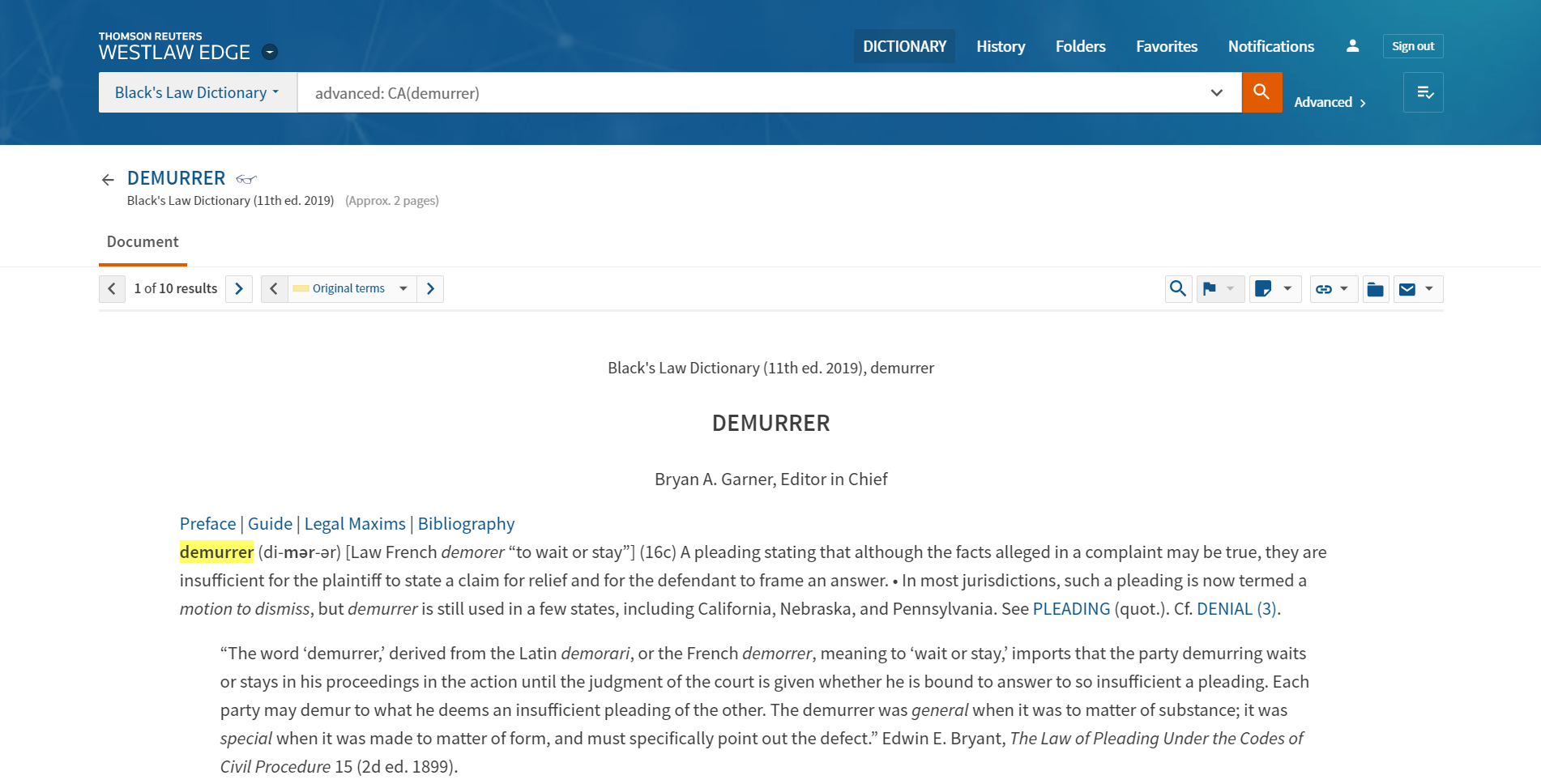

Civil Procedure: Rules & Guides

Know the rules. Enhance your understanding.

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rules & Commentary

Detailed, practical guidance on the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure from two leading experts, including a former member of the Civil Rules Advisory Committee.

Federal Civil Procedure Before Trial, National Edition

A procedural guide on pretrial practice in federal courts removal and remand, pleadings, motion practice and discovery, and all other pretrial stages of a lawsuit.

Federal Practice & Procedure

(Wright & Miller)

Comprehensive coverage of the jurisdiction of all federal courts, venue, removal of cases, res judicata, relation of state and federal courts, and more.

PRACTICAL LAW

Master Civil Procedure from jurisdiction to post-judgment.

A list of essential Practical Law resources to help you learn the basics of Federal Civil Procedure.

Black Letter Outline: Civil Procedure

POWERED BY QUIMBEE

5 min.

Case Brief Video:

Carabetta vs Carabetta

Rule of Law

A marriage is not rendered void under Connecticut law by virtue of the couple’s failure to obtain a statutorily required marriage license.

Carabetta Facts, Issue, & Holding

Rule of Law

A marriage is not rendered void under Connecticut law by virtue of the couple’s failure to obtain a statutorily required marriage license.

Facts

In 1955, Mr. Carabetta (defendant) and Mrs. Carabetta (plaintiff) exchanged vows in marriage before a Roman Catholic priest. They did not, however, obtain a statutorily required marriage license. They lived together and raised four children with all indications that they considered themselves legally married. Eventually Mrs. Carabetta filed for divorce. The trial court held that the marriage was void because the couple had never obtained a marriage license. The court then dismissed Mrs. Carabetta’s divorce petition for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction. She appealed.

Issue

Where a couple fails to obtain a marriage license but exchanges vows before a priest authorized to perform the marriage ceremony and then lives together and raises a family without any evidence that they do not consider themselves married, is the marriage void?

Holding and Reasoning (Peters, J.)

No. When the legislature has decided that the failure to meet a statutory requirement for marriage should render the marriage void, it has explicitly said so. For example, the law explicitly voids a marriage that is entered into between certain related persons. In contrast, the statute requiring a marriage license does not state that the failure to receive a license will make the marriage void. Rather, it states that the penalty for failing to obtain a license is a fine levied on the officiant who performed the marriage ceremony. This court has a long history of interpreting the absence of express statutory language. In line with such precedent, the court concludes here that a marriage entered into without a marriage license is dissoluble but not void. The court’s conclusion is supported by decisions in many other jurisdictions. Consequently, the trial court order is reversed.

Powered by Quimbee

Civil Procedure: Sample Exam

30 Minutes

Fact Pattern

A party is domiciled in the state where her true, fixed, and permanent home is located.

Facts

A painter is a citizen of State A. One day, while the painter is using a ladder, the rung on which the painter is standing collapses. The painter falls to the ground and sustains severe injuries. The accident occurs in State A.

The ladder’s manufacturer is incorporated under the laws of State A, where its corporate headquarters and ladder-manufacturing facility are both located. Ladder sales account for approximately 75 percent of the manufacturer’s annual revenue. The manufacturer has a network of authorized ladder dealers across the United States, including the store in State A where the painter purchased the ladder.

The manufacturer builds its ladders using components purchased from other companies. For the past ten years, the manufacturer has obtained all of its ladder rungs from a single supplier. The supplier is incorporated in State A, and its rung-production facility is located in State A. However, the supplier maintains a suite of offices in State B. These offices house the supplier’s president and CEO, its human-resources department, its chief financial officer, and its sales department. The manufacturer has several ladder dealers in State B, which collectively account for approximately two percent of the manufacturer’s annual revenue.

One month after the accident, the painter moves to State B. The painter purchases a house in State B, and he obtains a State B driver’s license. The painter’s injuries require four hours of physical therapy per week; the therapy is provided by a therapist in State B. These therapy sessions are expected to continue indefinitely.

The painter has filed suit against the manufacturer and the supplier in the United States District Court for the District of State B, seeking $200,000 in damages for personal injury. The long-arm statute of State B allows personal jurisdiction to the extent permitted by the United States Constitution. The manufacturer has moved to dismiss the case against it for lack of personal jurisdiction. The supplier has moved to dismiss the case against it for both lack of personal jurisdiction and lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.

Should the court grant the manufacturer’s motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction? Explain.

Should the court grant the manufacturer’s motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction? Explain.

The first question is whether the court should grant the manufacturer’s motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction. The answer is yes, because the manufacturer lacks sufficient contacts with State B to support personal jurisdiction.

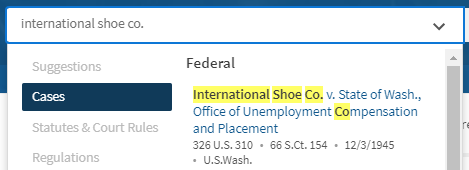

In general, a federal district court’s personal jurisdiction is the same as that of the state courts of general jurisdiction in the state where the federal court sits. A state court’s personal jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant is derived from the state’s long-arm statute, subject to the limits imposed by the Due Process Clause of the United States Constitution.

The manufacturer does not reside in State B, because it is incorporated in state A and has its principal place of business in State A. The painter must therefore rely on the State B long-arm statute, which permits personal jurisdiction to the limits of the U.S. Constitution. This, in turn, means that the manufacturer’s motion will depend on a due process analysis.

The Due Process Clause allows a state court to assert personal jurisdiction over a non-resident defendant who has sufficient minimum contacts with that state. The minimum contacts analysis examines the connections among the defendant, the forum state, and the litigation; the purpose is to determine whether the defendant has created connections with the forum state, such that the exercise of personal jurisdiction comports with traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice.

As part of this framework, personal jurisdiction can be divided into two types: specific jurisdiction and general jurisdiction. Specific jurisdiction applies where the cause of action arises out of the defendant’s contacts with the forum state. General jurisdiction applies where the defendant’s contacts with the forum state are so continuous and systematic that it can be sued there on any cause of action, even those that are unconnected to the forum.

The painter’s case against the manufacturer in State B does not involve specific jurisdiction, because none of the manufacturer’s contacts with State B had anything to do with the painter’s injury. Instead, the manufacture and sale of the ladder, plus the resulting injury, all occurred in State A. The painter must therefore rely on general jurisdiction to sue the manufacturer in State B.

The Supreme Court has held that general jurisdiction requires systematic and continuous contacts with the forum state, such that the defendant can be considered at home there. Examples of states with general jurisdiction include the state where the defendant is incorporated, and the state where the defendant has its principal place of business. The Court has not ruled out other grounds for general jurisdiction, but its recent cases appear to limit those grounds considerably. In Goodyear v. Brown, for example, the Court held that general jurisdiction did not exist where the defendant’s only connection with the forum was the sale of one industrial machine within that state. Further, in Daimler AG v. Bauman, the Court rejected a claim of general jurisdiction where the defendant’s only contact with the forum was a network of dealers.

These principles indicate that State B does not have general personal jurisdiction over the manufacturer. The manufacturer is incorporated and has its principal place of business in State A, not State B. The manufacturer’s sole contact with State B is a portion of its national dealer network, which accounts for only two percent of its annual revenue. The situation is directly analogous to Goodyear, which refused to find general jurisdiction based on minimal product sales. It is also analogous to Daimler, where a dealer network was held insufficient to support general jurisdiction. The vast majority of the manufacturer’s activities occur elsewhere, so in no sense can the manufacturer be said to be at home in State B. The federal court in State B therefore lacks personal jurisdiction over the manufacturer.

Not only does this conclusion align with Supreme Court precedent, but it is also consistent with traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice. Courts consider many factors to determine whether exercising personal jurisdiction is consistent with these notions, including: the burden on the defendant, the forum state’s interest in adjudicating the dispute, and the efficient operation of the interstate judicial system. These factors do not favor the painter’s attempt to sue the manufacturer in State B. The manufacturer’s home is State A, not State B, which suggests that litigating in State B will be less convenient for the manufacturer. Moreover, State B has no significant interest in adjudicating the case, because the case is based on events that occurred wholly in State A, before the painter moved to State B. Other than the painter’s personal convenience, judicial efficiency gains nothing by adjudicating the claim in State B. Indeed, it does not seem either fair or just to require a defendant to litigate in a state where none of the relevant events occurred, and where the defendant has little presence. Thus, traditional notions of fair play and substantial justice reinforce the conclusion that State B lacks personal jurisdiction over the manufacturer.

Nonetheless, the painter will argue that the painter’s own presence in State B should confer personal jurisdiction over the manufacturer. Specifically, the painter will contend that the manufacturer’s activities have caused an ongoing effect in State B, because the painter now lives there, and there he receives medical treatment arising from the accident. The painter will argue that this effect, in turn, is a meaningful contact that should be sufficient to support personal jurisdiction.

The painter will not prevail, however, because this very argument was rejected by the Supreme Court in Walden v. Fiore. In Walden, two plaintiffs, residents of Nevada, encountered a federal agent while traveling through Georgia, where the agent seized their property. The plaintiffs later sued the agent in Nevada. They argued that Nevada had personal jurisdiction because the agent’s activities, though carried out in Georgia, caused harm that continued to affect the plaintiffs in Nevada. The Court held that Nevada lacked personal jurisdiction over the agent, because the agent did not direct his actions specifically to Nevada. Rather, it was the plaintiffs’ own decision to be in Nevada that caused any effect to be felt within that state.

This case is analogous. The painter’s decision to move to State B was the painter’s alone, and had nothing to do with the manufacturer. The fact that the painter may continue to feel the effects of the injury and receive treatment in State B does not mean that the manufacturer ever directed its relevant conduct toward State B. As in Walden, the unilateral acts of the plaintiff cannot alone confer jurisdiction over the defendant.

The court should therefore grant the manufacturer’s motion and dismiss the case against the manufacturer for lack of personal jurisdiction.

Should the court grant the supplier’s motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction? Explain.

The next question is whether the court should grant the supplier’s motion to dismiss for lack of personal jurisdiction. The court should deny the motion, because State B has personal jurisdiction over the supplier.

Personal jurisdiction over the supplier could be justified in one of two ways. First, a state always has personal jurisdiction over citizens of that state, apart from any minimum contacts analysis. Even under minimum contacts, as explained above, a state has general jurisdiction over a corporate defendant in the state where the corporation has its principal place of business. Either analysis would support personal jurisdiction over the supplier in State B.

A corporation is a citizen of both the state where it is incorporated and the state where it has its principal place of business, even if these are two different states. The supplier is incorporated in State A, but its principal place of business is in State B. This makes the supplier a citizen of both State A and State B.

A corporation’s principal place of business is determined by the nerve center test, which asks where the corporation’s high-level executives coordinate and control its activities. While the supplier manufactures products in State A, this manufacture does not constitute high-level corporate decision-making. The supplier’s executive functions are centered at the State B offices, which include the company’s president and CEO, as well as its human resources, finance, and sales offices. The nerve center test points strongly to State B as the supplier’s principal place of business, making the supplier a citizen of State B. As a citizen of State B, the supplier is subject to State B’s general jurisdiction, and the court should therefore deny the supplier’s motion to dismiss.

Personal jurisdiction could also be supported under a minimum contacts analysis, though this is somewhat redundant. As explained above, a state has general personal jurisdiction over a corporation that has its principal place of business in that state. Again, the supplier’s principal place of business is in state B, which gives State B personal jurisdiction even aside from the question of citizenship.

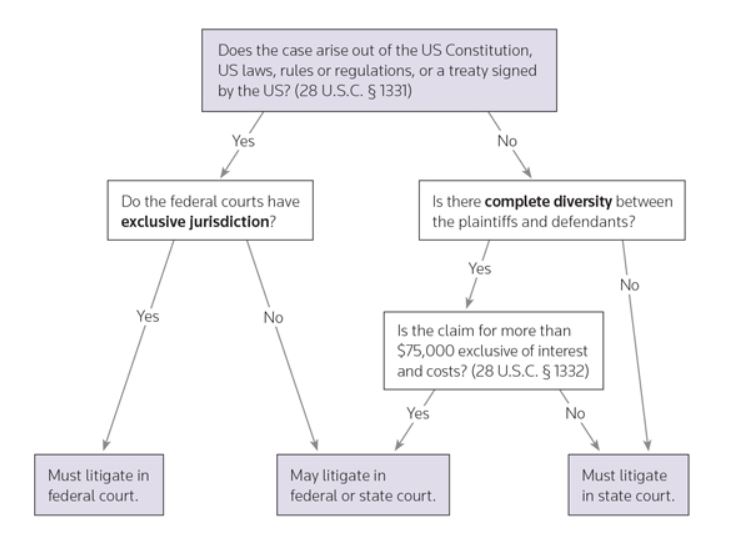

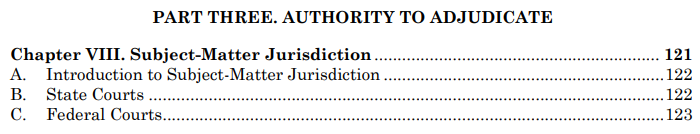

Should the court grant the supplier’s motion to dismiss for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction? Explain.

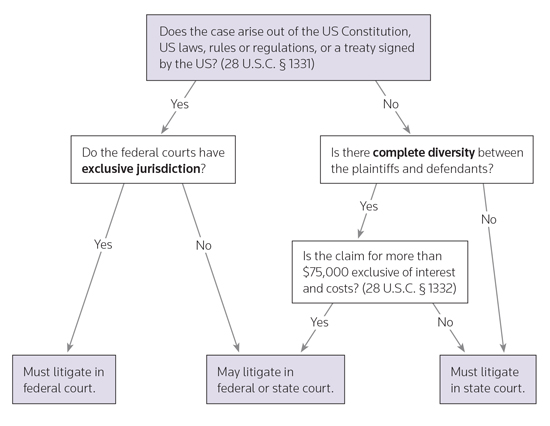

The final question is whether the court should grant the supplier’s motion to dismiss for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction. The court should grant the motion, because the requirements for diversity of citizenship are not met.

The painter’s claim arises under state tort law, and the painter must therefore rely on diversity jurisdiction in order to bring his claim in federal court. The federal diversity statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1332, permits federal jurisdiction when the plaintiff and defendant are citizens of different states, and the amount in controversy is greater than $75,000. The statute requires complete diversity, meaning that all defendants must be diverse from all plaintiffs.

While the painter’s claim exceeds $75,000, there is not complete diversity of citizenship because both the painter and the supplier are citizens of State B. For diversity purposes, an individual is a citizen of the state where the individual is domiciled; that is, where the individual lives and intends to reside indefinitely. Moreover, citizenship is determined as of the time the suit is filed, not as of the time the claim arose. The painter was injured in State A, but before filing suit, the painter moved to State B. By all indications (including the purchase of a new house and the obtaining of a new driver’s license), the painter intends to remain in State B indefinitely. The painter is therefore a citizen of State B for purposes of diversity jurisdiction.

As explained above, the supplier is also a citizen of State B, because State B is where it has its principal place of business. This means that complete diversity of citizenship is lacking, and the court should therefore grant the supplier’s motion to dismiss for lack of subject-matter jurisdiction.

The painter might argue that the claim against the supplier falls within the court’s supplemental jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. § 1367. That argument would fail. Supplemental jurisdiction can be used when a case includes multiple claims, some of which would otherwise fall outside the court’s subject-matter jurisdiction. Under Section 1367, the court has the power to hear such claims if they form part of the same case or controversy as a claim over which the court already has subject-matter jurisdiction. Courts sometimes hold that claims are part of the same case or controversy when they share a common nucleus of operative fact, or arise from a single transaction or occurrence.

Applying these concepts, the painter would first point out that the claim against the manufacturer falls within diversity jurisdiction. Diversity of citizenship exists for that claim because the manufacturer is a citizen of State A, where it is incorporated and where it has its principal place of business, while the painter is a citizen of State B. Further, the amount in controversy is greater than $75,000. The painter would then argue that the claim against the supplier is part of the same case or controversy as the claim against the manufacturer, because both claims are based on the same occurrence, that is, the collapse of the ladder and the painter’s injury. Supplemental jurisdiction, so the argument goes, would therefore apply to the painter’s claim against the supplier.

This argument, however, ignores an important limitation on supplemental jurisdiction. Section 1367(b) provides that in a case founded on diversity jurisdiction, supplemental jurisdiction will not apply to claims made by plaintiffs against defendants if allowing those claims would be inconsistent with the requirements of Section 1332, including complete diversity. The painter’s case exemplifies this restriction. If the painter could join the non-diverse supplier, then the case would include a State B plaintiff (the painter) against a State A defendant (the manufacturer) and a State B defendant (the supplier). Complete diversity of citizenship would be lacking, and the painter would have effectively circumvented the complete diversity requirement. This is exactly the result that Section 1367(b) was designed to prevent, and thus the painter’s claim against the supplier will not fall under supplemental jurisdiction.

Yeah, we love Quimbee too.

We've partnered with Quimbee to bring you content on this page. They make law school study aids, bar prep, and CLE courses you'll actually enjoy.